The impact of entrepreneurship education on university students’ entrepreneurial skills: a family embeddedness perspective

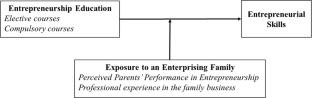

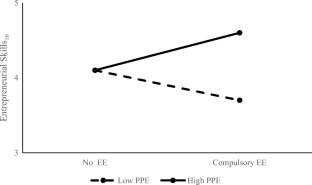

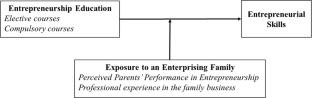

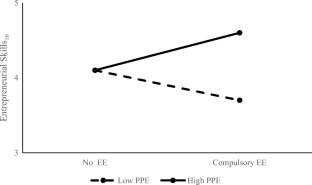

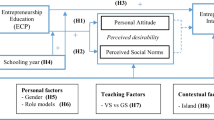

To provide individuals with entrepreneurial skills and prepare them to engage in entrepreneurial activities, universities offer entrepreneurship education (EE) courses. However, the growing number of studies on EE impact offers mixed and apparently contradictory results. The present study contributes to this literature by indicating the type of EE (elective vs. compulsory) and the characteristics of students’ exposure to an enterprising family as two complementary boundary conditions that contribute to explain the outcomes of EE. To do so, the paper takes advantage of quasi-experimental research on a sample of 427 university students who participated to two consecutive waves of the Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students’ Survey (GUESSS). The study finds that both types of EE contribute to students’ entrepreneurial skills; however, the impact of EE in compulsory courses is contingent on students’ perceptions of parents’ performance as entrepreneurs.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save

Springer+ Basic

€32.70 /Month

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Buy Now

Price includes VAT (France)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of entrepreneurship education on students’ desirability and intentions to pursue an entrepreneurial career: a study in general and vocational secondary schools of Cabo Verde

Article Open access 06 June 2024

Entrepreneurship education and graduate’s venture creation activities: roles of entrepreneurial support and entrepreneurial capabilities

Article 23 May 2023

Does entrepreneurship education matter? Business students’ perspectives

Article 01 December 2017

Notes

A full description of the GUESSS project is available at the website www.guesssurvey.org. Several works based on the GUESSS project have already been published in entrepreneurship journals: see, for example, Bergmann et al. (2016); Minola, Donina, and Meoli (2016); and Sieger and Minola (2017).

The inclusion of the lagged values of the dependent variables raises concerns related to the potential autocorrelation in the error terms. The Cumby and Huizinga (1992) statistic is applied to test for autocorrelation of order 1 in the residuals under the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation. The statistic rejects the null hypothesis of entrepreneurial skills being serially uncorrelated (χ 2 = 169.062, p < 0.001) and shows that serial correlation between the dependent variable and its lagged value is correctly specified at degree 1.

VIF values above 5 were found only for the dummy variables bachelor and master because together they cover 96% of the sample and are thus highly correlated (− 0.90). By dropping the variable bachelor and keeping undergraduate students as reference category, VIFs remained below 2 with results substantially unchanged.

In support to this idea, the model was also run with robust standard errors, not clustered by university. In this model, the coefficient of EE was positive and statistically significant (β = 0.203, p < 0.10). Moreover, we run a model without university fixed effects, and it was found that the coefficients of EE in elective (β = 0.262, p < 0.05) and compulsory (β = 0.224, p < 0.10) courses were both positive and statistically significant. To gain further insights into the different effects produced by EE in elective and in compulsory EE, we also separately focused on compulsory EE vs. no EE and on elective EE vs. no EE: in the first case, entrepreneurial skills were regressed on EE in compulsory courses, leaving students with no EE as baseline and excluding from the sample students who received EE in elective courses; in the latter case, entrepreneurial skills were regressed on EE in elective courses, leaving students with no EE as baseline and excluding from the sample students who received EE in compulsory courses. In both cases, the university fixed effects were included. In these specifications, the coefficient of EE in elective (β = 0.358, p < 0.05) remains positive and significant, while the coefficient of compulsory EE remains positive albeit not significant.

Applying the Oster (2017) procedure (cf. Lyons and Zhang 2018), support is found to the need to control for potential endogeneity due to unobservables (correlated both to selection into EE and to outcomes of EE). Additionally, both the Wu-Hausman test and Durbin-Wu-Hausman statistics reject the null hypothesis that the EE indicator is not exogenous.

To measure variables at the local level that might affect students’ entrepreneurial learning, periods of multiple years have already been used in empirical models aimed at quantitatively assessing the impact of EE (cf. Hahn et al. 2017).

In the first stage, using a probit estimator, the EE indicators on the instrument are regressed to obtain predicted values that contain the variation in the EE indicators uncorrelated with the error terms. Then, in the second stage, the dependent variable, entrepreneurial skills, is regressed on predicted values defined in the first stage, applying a two-stage least squares estimator. Concerning the instrument relevance, first-stage estimates suggest that the instrument and the EE indicators are negatively correlated and that the degree of correlation rises as university fixed effects are introduced in the first-stage regression.

As described in Section 3.1, the complete longitudinal GUESSS 2013–2016 dataset records the answers from 1383 students from 21 countries, but the present analysis includes only questionnaires of those students who in the 2013 survey reported not having attended EE before. The sample also excludes students who attended EE in both elective and compulsory EE, students from countries whose number of complete responses was below 5, and respondents for whom it was not possible to build the variables of interest.

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage. Google Scholar

- Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: toward a family embeddedness perspective. J Bus Ventur, 18(5), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Audretsch, D. B. (2014). From the entrepreneurial university to the university for the entrepreneurial society. J Technol Transf, 39(3), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9288-1. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2013). The missing pillar: the creativity theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ, 41(4), 819–836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9508-6. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Audretsch, D. B., & Lehmann, E. E. (2005). Do university policies make a difference? Res Policy, 34(3), 343–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.006. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: a meta-analytic review. Entrep Theory Pract, 38(2), 217–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12095. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bascle, G. (2008). Controlling for endogeneity with instrumental variables in strategic management research. Strateg Organ, 6(3), 285–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127008094339. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Béchard, J. P., & Grégoire, D. (2005). Entrepreneurship education research revisited: the case of higher education. Acad Manag Learn Educ, 4(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.16132536. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bergmann, H., Hundt, C., & Sternberg, R. (2016). What makes student entrepreneurs? On the relevance (and irrelevance) of the university and the regional context for student start-ups. Small Bus Econ, 47(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9700-6. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bergmann, H., Geissler, M., Hundt, C., & Grave, B. (2018). The climate for entrepreneurship at higher education institutions. Res Policy, 47(4), 700–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.01.018. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Binder, M., & Coad, A. (2013). Life satisfaction and self-employment: a matching approach. Small Bus Econ, 40(4), 1009–1033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9413-9. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bird, B., Schjoedt, L., & Baum, J. R. (2012). Editor’s introduction. Entrepreneurs’ behavior: elucidation and measurement. Entrep Theory Pract, 36(5), 889–913. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00535.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Block, J., Thurik, R., Van der Zwan, P., & Walter, S. (2013). Business takeover or new venture? Individual and environmental determinants from a cross-country study. Entrep Theory Pract, 37(5), 1099–1121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00521.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., & Reynolds, P. D. (1996). Exploring start-up event sequences. J Bus Ventur, 11(3), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(95)00129-8. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chang, J., & Rieple, A. (2013). Assessing students’ entrepreneurial skills development in live projects. J Small Bus Enterp Dev, 20(1), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001311298501. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J Bus Ventur, 13(4), 295–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00029-3. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Chlosta, S., Patzelt, H., Klein, S. B., & Dormann, C. (2012). Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: the moderating effect of personality. Small Bus Econ, 38(1), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9270-y. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Erlbaum. Google Scholar

- Cope, J. (2005). Toward a dynamic learning perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract, 29(4), 373–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00090.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Criaco, G., Sieger, P., Wennberg, K., Chirico, F., & Minola, T. (2017). Parents’ performance in entrepreneurship as a “double-edged sword” for the intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ, 49(4), 841–864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9854-x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Cumby, R. E., & Huizinga, J. (1992). Investigating the correlation of unobserved expectations: expected returns in equity and foreign exchange markets and other examples. J Monet Econ, 30(2), 217–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(92)90061-6. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dodd, S. D., & Hynes, B. C. (2012). The impact of regional entrepreneurial contexts upon enterprise education. Entrepr Reg Dev, 24(9–10), 741–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2011.566376. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Eddleston, K. A., Kellermanns, F. W., & Sarathy, R. (2008). Resource configuration in family firms: linking resources, strategic planning and technological opportunities to performance. J Manag Stud, 45(1), 26–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00717.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fayolle, A. (2013). Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. Entrep Reg Dev, 25(7–8), 692–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2013.821318. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: hysteresis and persistence. J Small Bus Manag, 53(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12065. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Grilo, I., & Thurik, R. (2008). Determinants of entrepreneurial engagement levels in Europe and the US. Ind Corp Chang, 17(6), 1113–1145. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtn044. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Haase, H., & Lautenschläger, A. (2011). The ‘teachability dilemma’ of entrepreneurship. Int Entrep Manag J, 7(2), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-010-0150-3. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hahn, D., Minola, T., Van Gils, A., & Huybrechts, J. (2017). Entrepreneurial education and learning at universities: exploring multilevel contingencies. Entrep Reg Dev, 29(9–10), 945–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1376542. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hamilton, E. (2011). Entrepreneurial learning in family business: a situated learning perspective. J Small Bus Enterp Dev, 18(1), 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001111106406. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hoffmann, A., Junge, M., & Malchow-Møller, N. (2015). Running in the family: parental role models in entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ, 44(1), 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9586-0. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Honig, B. (2004). Entrepreneurship education: toward a model of contingency-based business planning. Acad Manag Learn Educ, 3(3), 258–273. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2004.14242112. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hytti, U., Stenholm, P., Heinonen, J., & Seikkula-Leino, J. (2010). Perceived learning outcomes in entrepreneurship education: the impact of student motivation and team behaviour. Educ Train, 52(8/9), 587–606. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011088935. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., & Rau, S. B. (2015). Entrepreneurial legacy: toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. J Bus Ventur, 30(1), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.001. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., Ketchen, D. J., & Ireland, R. D. (2016). Enduring entrepreneurship: antecedents, triggering mechanisms, and outcomes. Strateg Entrep J, 10(4), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1234. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kacperczyk, A. J. (2013). Social influence and entrepreneurship: the effect of university peers on entrepreneurial entry. Organ Sci, 24(3), 664–683. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1120.077. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kacperczyk, A., & Marx, M. (2016). Revisiting the small-firm effect on entrepreneurship: evidence from firm dissolutions. Organ Sci, 27(4), 893–910. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2016.1065. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Karimi, S., Biemans, H. J., Lans, T., Chizari, M., & Mulder, M. (2016). The impact of entrepreneurship education: a study of Iranian students’ entrepreneurial intentions and opportunity identification. J Small Bus Manag, 54(1), 187–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12137. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Karlsson, T., & Moberg, K. (2013). Improving perceived entrepreneurial abilities through education: exploratory testing of an entrepreneurial self efficacy scale in a pre-post setting. Int J Manag Educ, 11(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2012.10.001. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kennedy, P. (2008). A guide to econometrics. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. Google Scholar

- Kickul, J., Gundry, L. K., Barbosa, S. D., & Whitcanack, L. (2009). Intuition versus analysis? Testing differential models of cognitive style on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the new venture creation process. Entrep Theory Pract, 33(2), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/2Fj.1540-6520.2009.00298.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kuratko, D. F. (2005). The emergence of entrepreneurship education: development, trends, and challenges. Entrep Theory Pract, 29(5), 577–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00099.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Laskovaia, A., Shirokova, G., & Morris, M. H. (2017). National culture, effectuation, and new venture performance: global evidence from student entrepreneurs. Small Bus Econ, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9852-z.

- Laspita, S., Breugst, N., Heblich, S., & Patzelt, H. (2012). Intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial intentions. J Bus Ventur, 27(4), 414–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.11.006. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Laukkanen, M. (2000). Exploring alternative approaches in high-level entrepreneurship education: creating micromechanisms for endogenous regional growth. Entrep Reg Dev, 12(1), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/089856200283072. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Leitch, C., Hazlett, S. A., & Pittaway, L. (2012). Entrepreneurship education and context. Entrep Reg Dev, 24(9–10), 733–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2012.733613. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep Theory Pract, 33(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Liñán, F., & Fernandez-Serrano, J. (2014). National culture, entrepreneurship and economic development: different patterns across the European Union. Small Bus Econ, 42(4), 685–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9520-x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lyons, E., & Zhang, L. (2018). Who does (not) benefit from entrepreneurship programs? Strateg Manag J, 39(1), 85–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2704. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Martin, B. C., McNally, J. J., & Kay, M. J. (2013). Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneurship: a meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. J Bus Ventur, 28(2), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.03.002. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- McGee, J. E., Peterson, M., Mueller, S. L., & Sequeira, J. M. (2009). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: refining the measure. Entrep Theory Pract, 33(4), 965–988. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00304.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Memili, E., Fang, H., Chrisman, J. J., & De Massis, A. (2015). The impact of small-and medium-sized family firms on economic growth. Small Bus Econ, 45(4), 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9670-0. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Minola, T., Criaco, G., & Cassia, L. (2014). Are youth really different? New beliefs for old practices in entrepreneurship. Int J Entrep Innov Manag, 18(2-3), 233–259. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEIM.2014.062881. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Minola, T., Brumana, M., Campopiano, G., Garrett, R. P., & Cassia, L. (2016a). Corporate venturing in family business: a developmental approach of the enterprising family. Strateg Entrep J, 10(4), 395–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1236. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Minola, T., Donina, D., & Meoli, M. (2016b). Students climbing the entrepreneurial ladder: does university internationalization pay off? Small Bus Econ, 47(3), 565–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9758-1. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Morris, M. H., Shirokova, G., & Tsukanova, T. (2017). Student entrepreneurship and the university ecosystem: a multi-country empirical exploration. Eur J Int Manag, 11(1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2017.081251. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mueller, S., & Anderson, A. R. (2014). Understanding the entrepreneurial learning process and its impact on students’ personal development: a European perspective. Int J Manag Educ, 12(3), 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.05.003. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mungai, E., & Velamuri, S. R. (2011). Parental entrepreneurial role model influence on male offspring: is it always positive and when does it occur? Entrep Theory Pract, 35(2), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00363.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mustar, P. (2009). Technology management education: innovation and entrepreneurship at MINES ParisTech, a leading French engineering school. Acad Manag Learn Educ, 8(3), 418–425. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.8.3.zqr418. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: a systematic review and research agenda. Acad Manag Learn Educ, 16(2), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0026. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Naia, A., Baptista, R., Januário, C., & Trigo, V. (2014). A systematization of the literature on entrepreneurship education: challenges and emerging solutions in the entrepreneurial classroom. Ind High Educ, 28(2), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.5367/ihe.2014.0196. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Neck, H. M., & Greene, P. G. (2011). Entrepreneurship education: known worlds and new frontiers. J Small Bus Manag, 49(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00314.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw Hill. Google Scholar

- Oosterbeek, H., Van Praag, M., & Ijsselstein, A. (2010). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. Eur Econ Rev, 54(3), 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.08.002. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Oster, E. (2017). Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: theory and evidence. J Bus Econ Stat, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2016.1227711.

- Peterman, N. E., & Kennedy, J. (2003). Enterprise education: influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract, 28(2), 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1540-6520.2003.00035.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Politis, D. (2005). The process of entrepreneurial learning: a conceptual framework. Entrep Theory Pract, 29(4), 399–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00091.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2008). Generalized linear mixed effects models. In G. Fitzmaurice, M. Davidian, G. Verbeke, & G. Molenberghs (Eds.), Longitudinal data analysis: a handbook of modern statistical methods (pp. 79–106). Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC. Google Scholar

- Rauch, A., & Hulsink, W. (2015). Putting entrepreneurship education where the intention to act lies: an investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Acad Manag Learn Educ, 14(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0293. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rideout, E. C., & Gray, D. O. (2013). Does entrepreneurship education really work? A review and methodological critique of the empirical literature on the effects of university-based entrepreneurship education. J Small Bus Manag, 51(3), 329–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12021. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rogoff, E. G., & Heck, R. K. Z. (2003). Evolving research in entrepreneurship and family business: recognizing family as the oxygen that feeds the fire of entrepreneurship. J Bus Ventur, 18(5), 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00009-0. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Salvato, C., Sharma, P., & Wright, M. (2015). From the guest editors: learning patterns and approaches to family business education around the world—issues, insights, and research agenda. Acad Manag Learn Educ, 14(3), 307–320. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sánchez, J. C. (2011). University training for entrepreneurial competencies: its impact on intention of venture creation. Int Entrep Manag J, 7(2), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-010-0156-x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Shah, S. K., & Pahnke, E. C. (2014). Parting the ivory curtain: understanding how universities support a diverse set of startups. J Technol Transf, 39(5), 780–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-014-9336-0. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Shepherd, D., & Haynie, J. M. (2009). Family business, identity conflict, and an expedited entrepreneurial process: a process of resolving identity conflict. Entrep Theory Pract, 33(6), 1245–1264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00344.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Shinnar, R., Pruett, M., & Toney, B. (2009). Entrepreneurship education: attitudes across campus. J Educ Bus, 84(3), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.84.3.151-159. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sieger, P., & Minola, T. (2017). The family’s financial support as a “poisoned gift”: a family embeddedness perspective on entrepreneurial intentions. J Small Bus Manag, 55(S1), 179–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12273. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S., & Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. J Bus Ventur, 22(4), 566–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.05.002. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Toutain, O., Fayolle, A., Pittaway, L., & Politis, D. (2017). Role and impact of the environment on entrepreneurial learning. Entrep Reg Dev, 29(9–10), 869–888. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1376517. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Uy, M. A., Foo, M. D., & Song, Z. (2013). Joint effects of prior start-up experience and coping strategies on entrepreneurs’ psychological well-being. J Bus Ventur, 28(5), 583–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.04.003. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Volery, T., Müller, S., Oser, F., Naepflin, C., & Rey, N. (2013). The impact of entrepreneurship education on human capital at upper-secondary level. J Small Bus Manag, 51(3), 429–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12020. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- von Graevenitz, G., Harhoff, D., & Weber, R. (2010). The effects of entrepreneurship education. J Econ Behav Organ, 76(1), 90–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2010.02.015. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Walter, S. G., & Block, J. H. (2016). Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: an institutional perspective. J Bus Ventur, 31(2), 216–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.10.003. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Walter, S. G., & Dohse, D. (2012). Why mode and regional context matter for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 24(9–10), 807–835 https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2012.721009. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wilson, G., & McCrystal, P. (2007). Motivations and career aspirations of MSW students in Northern Ireland. Soc Work Educ, 26(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470601036534. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: implications for entrepreneurship education 1. Entrep Theory Pract, 31(3), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00179.x. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zhou, J., & George, J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: encouraging the expression of voice. Acad Manag J, 44(4), 682–696. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069410. ArticleGoogle Scholar

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the organizers and participants of the Workshop Knowledge Frontiers and Knowledge Boundaries in Europe (Bozen, October 2017) where we received insightful comments that helped us to refine this paper. We are grateful also for the suggestions offered at the 28th Riunione Scientifica Annuale Associazione italiana di Ingegneria Gestionale (Bari, October 2017), the Technology Transfer Society Annual Conference (Washington, November 2017), and at the International Research Conference on Science and Technology Entrepreneurship Education (Toulouse, April 2017) where earlier versions of the manuscript have been presented.

Funding

Support for this research was provided by the “Campus Entrepreneurship” project, financed by the University of Bergamo through the “Excellence Initiative” funding scheme, and by the Italian Ministry of Education and Research through the “Contamination Lab” funding scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Management, Information and Production Engineering, University of Bergamo, Via Pasubio 7b, 24044, Dalmine, BG, Italy Davide Hahn, Tommaso Minola & Lucio Cassia

- Center for Young and Family Enterprise, University of Bergamo, Via Salvecchio 19, 24127, Bergamo, BG, Italy Davide Hahn, Tommaso Minola, Giulio Bosio & Lucio Cassia

- Department of Management, Economics and Quantitative Methods, University of Bergamo, Via dei Caniana 2, 24127, Bergamo, BG, Italy Giulio Bosio

- Davide Hahn